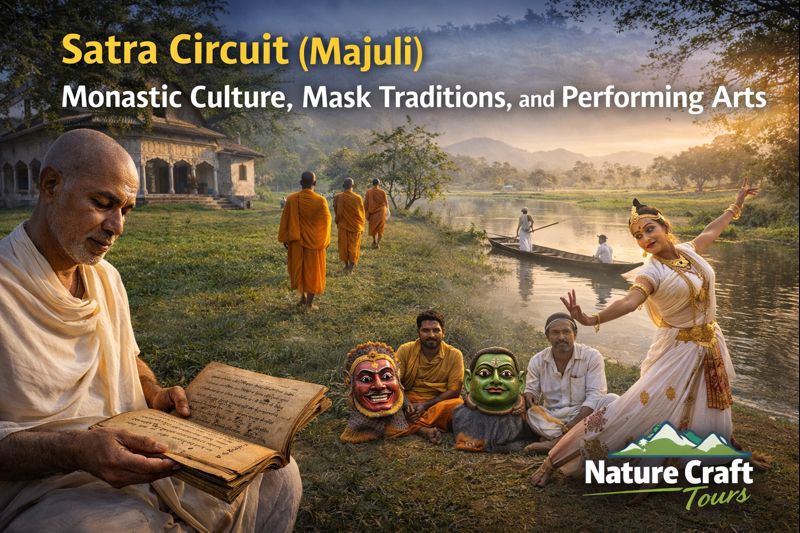

Satra Circuit (Majuli):

Monastic Culture, Mask Traditions, and Performing Arts

The Satra Circuit of Majuli represents one of the most intellectually rich and culturally intact monastic landscapes in South Asia. Set within the fragile geography of the Brahmaputra River’s shifting channels, this circuit is not a conventional travel route but a contemplative journey through living institutions where religion, art, performance, and daily life remain inseparably intertwined. To walk through Majuli’s Satras is to witness a civilization sustained not by monuments or empires, but by discipline, artistic continuity, and collective memory. The experience unfolds slowly—through morning prayers echoing across courtyards, the rhythmic footwork of Sattriya dance rehearsals, the scent of wet bamboo and clay masks drying in shaded workshops, and the quiet scholarship preserved in handwritten manuscripts.

This is not a destination shaped for spectacle. The Satra Circuit demands time, attentiveness, and respect, rewarding travelers with insights into a monastic culture that has survived floods, political change, and modern disinterest without losing its philosophical core. Majuli’s Satras are not relics of the past; they are functioning cultural ecosystems, and exploring them is an exercise in understanding how spiritual institutions can anchor society across centuries.

Majuli and the Concept of the Satra Circuit

Majuli, located in the upper Brahmaputra valley of Assam, is globally known as one of the largest inhabited river islands. However, its deeper importance lies not in geographical records but in its role as the spiritual heartland of Neo-Vaishnavism in eastern India. The Satra Circuit refers to a loosely connected network of monastic institutions established from the 15th century onward, primarily under the guidance of the saint-reformer Srimanta Sankardeva and his principal disciples.

Unlike pilgrimage circuits defined by sacred sites alone, the Satra Circuit is experiential. Each Satra functions as a center for religious instruction, artistic production, social regulation, and cultural transmission. Together, they form a decentralized yet philosophically unified network that shapes Majuli’s identity. Traveling this circuit involves moving between Satras, villages, workshops, and performance spaces, tracing the living continuity of a belief system expressed through art and discipline.

Historical Foundations of the Satra System

The Neo-Vaishnavite Movement

The origins of the Satra system lie in the Neo-Vaishnavite movement initiated in Assam during the 15th century. At a time marked by rigid caste hierarchies and ritual orthodoxy, the movement emphasized devotion (bhakti), ethical conduct, and community participation over ceremonial complexity. The Satras emerged as institutional expressions of this philosophy, designed to foster moral education, artistic engagement, and collective worship.

These institutions rejected exclusivity, welcoming disciples from diverse social backgrounds. Over time, Satras evolved distinct identities, shaped by regional contexts, leadership traditions, and artistic priorities. Yet all shared a commitment to preserving religious teachings through performative and literary means rather than doctrinal rigidity.

Majuli as a Monastic Capital

Majuli’s isolation and fertile landscape made it an ideal location for monastic settlement. Protected by river channels and sustained by agriculture, the island allowed Satras to develop with minimal external disruption. By the 17th century, Majuli had become a dense monastic zone, housing dozens of Satras that collectively shaped Assam’s religious and cultural life.

Despite erosion and displacement over the centuries, Majuli remains a symbolic monastic capital. Even Satras that have relocated to the mainland continue to trace their lineage and authority back to the island, underscoring its enduring spiritual significance.

Architectural and Spatial Character of Satras

Satra architecture is deliberately austere. Buildings are typically arranged around an open courtyard, with prayer halls, living quarters, performance spaces, and storage areas positioned to facilitate communal life. Ornamentation is minimal, emphasizing functionality and symbolic clarity over visual excess.

This spatial organization reflects monastic values of discipline and equality. The courtyard serves as a multipurpose space—hosting prayers, theatrical performances, assemblies, and festivals. The absence of hierarchical spatial divisions reinforces the Satra’s role as a collective institution rather than a shrine-centered complex.

Mask Traditions: Crafting Identity and Myth

Origins of Mask-Making in Satras

One of the most distinctive cultural expressions within the Satra Circuit is the tradition of mask-making, particularly associated with Ankiya Naat, the devotional theatre form developed under Sankardeva’s guidance. Masks are not decorative artifacts; they are narrative instruments, embodying mythological characters, moral archetypes, and cosmic forces.

The craft developed within monastic settings, where monks and artisans collaborated to produce masks using bamboo frameworks, clay, cloth, and natural pigments. Each mask is designed for performance durability rather than permanence, reinforcing the idea that art exists to serve spiritual communication rather than material legacy.

Samaguri and the Living Craft Tradition

Among Majuli’s Satras, Samaguri has become internationally recognized for its mask tradition. Workshops here operate as both production spaces and learning centers, where techniques are transmitted through apprenticeship rather than formal instruction. The process—from bamboo splitting to final pigment application—is deeply ritualized, aligning craftsmanship with devotional practice.

Observing mask creation offers insight into how mythological narratives are internalized and materialized. The exaggerated features of demons, deities, and animals are carefully calibrated for stage visibility, transforming abstract moral concepts into immediate visual language.

Performing Arts of the Satra Circuit

Sattriya Dance as Monastic Discipline

Sattriya dance, recognized today as one of India’s classical dance forms, originated within the Satras as a disciplined mode of devotional expression. Unlike courtly dance traditions, Sattriya evolved in monastic settings, where performance was integrated into religious observance rather than entertainment.

Training emphasizes precision, restraint, and narrative clarity. Movements are codified to convey theological themes, with equal attention given to rhythm, gesture, and emotional restraint. Performances often coincide with religious festivals, reinforcing the dance’s role as a living ritual rather than a staged spectacle.

Ankiya Naat: Theatre as Teaching

Ankiya Naat remains central to the Satra Circuit’s cultural life. These one-act plays, written in a blend of Assamese and Brajavali, dramatize episodes from Vaishnavite texts. Performances combine dialogue, music, dance, and masks to create immersive moral narratives accessible to all audiences.

Unlike commercial theatre, Ankiya Naat is community-centered. Performers are often monks or trained villagers, and performances are staged in open courtyards without elaborate sets. This simplicity enhances the focus on narrative and ethical instruction.

Ecological Context and Cultural Resilience

The Satra Circuit exists within an ecologically volatile environment. Majuli’s landmass continues to shrink due to riverbank erosion, displacing communities and Satras alike. Yet this instability has fostered resilience rather than decline. Monastic institutions have adapted by relocating structures, preserving manuscripts, and reestablishing practices without losing continuity.

This dynamic mirrors other riverine cultural landscapes in India, where human settlement negotiates constant environmental change. Similar adaptive strategies can be observed in delta regions explored through journeys such as a Sundarban Tour, highlighting shared challenges of sustainability and cultural preservation.

Planning a Journey Through the Satra Circuit

Best Time and Season to Travel

The most suitable period for exploring the Satra Circuit is from October to March. During these months, water levels stabilize, ferry services remain reliable, and cultural activities are more accessible. Winter festivals and rehearsal cycles offer opportunities to observe performing arts in their authentic contexts.

Ideal Travel Duration

A comprehensive exploration of the Satra Circuit requires at least three to four days. This allows time to visit multiple Satras, attend rehearsals or performances, engage with artisans, and observe daily monastic routines. Shorter visits risk reducing the experience to superficial observation.

Route and Accessibility

Majuli is accessed via ferry from Jorhat, which serves as the primary gateway. The ferry crossing itself is an integral part of the journey, emphasizing the island’s separation from the mainland. Once on Majuli, travel between Satras is typically by road, often through rural landscapes shaped by agriculture and wetlands.

Key Attractions Within the Satra Circuit

Major Satras such as Auniati, Kamalabari, Dakhinpat, and Samaguri each offer distinct perspectives on monastic life. Manuscript collections, prayer rituals, dance rehearsals, and mask workshops provide layered experiences rather than single highlights.

Village interactions, pottery clusters, and weaving practices complement Satra visits, illustrating how monastic culture extends into everyday life. Seasonal festivals transform the circuit into a shared cultural space, drawing participants from across Assam.

Practical Insights for Responsible Travelers

Visitors should approach the Satra Circuit with cultural sensitivity and patience. Photography may be restricted during rituals, and permission should always be sought. Modest attire and respectful conduct are essential, particularly within prayer spaces.

Infrastructure remains basic, and travel schedules are influenced by weather and river conditions. Accepting these limitations is part of understanding Majuli’s lived reality. Travelers familiar with ecologically sensitive destinations, such as those included in a Sundarban Tour Package, will recognize the importance of flexibility and environmental awareness.

Cultural Significance Beyond Majuli

The Satra Circuit’s influence extends far beyond Majuli. Sattriya dance, Ankiya Naat, and Neo-Vaishnavite philosophy have shaped Assam’s broader cultural identity, influencing music, literature, and social ethics. Majuli serves as the ideological and historical anchor for these traditions, even as they adapt to contemporary contexts.

The Satra Circuit as a Living Heritage

The Satra Circuit of Majuli is not a static heritage site but a living continuum of faith, art, and communal discipline. Its significance lies in its ability to sustain cultural practices through participation rather than preservation alone. Monastic culture here survives not because it is protected, but because it is practiced daily.

For travelers seeking depth over display, the Satra Circuit offers an encounter with one of India’s most quietly profound cultural landscapes. It invites observation, reflection, and humility, reminding visitors that true heritage endures not through permanence of place, but through continuity of purpose.