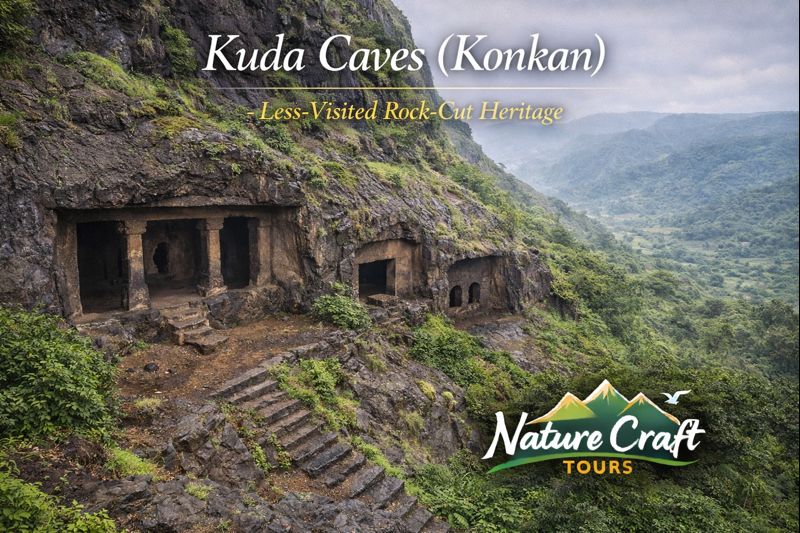

Kuda Caves (Konkan)

— Less-Visited Rock-Cut Heritage Hidden in the Coastal Hills

Along the quieter backroads of Maharashtra’s Konkan coast, away from crowded beaches and well-publicized monuments, lies a cluster of rock-cut caves that reward those who seek depth rather than display. The Kuda Caves, carved into a low basalt hill overlooking rural settlements and seasonal greenery, represent one of the Konkan’s most understated yet historically layered heritage sites. These caves do not dominate the landscape through scale or ornamentation; instead, they invite slow engagement—through stone surfaces shaped by hand, spatial simplicity refined by purpose, and a setting that merges archaeology with living countryside.

Kuda Caves occupy a liminal space between history and anonymity. Unlike more famous cave complexes of western India, Kuda remains largely absent from mainstream itineraries. This relative obscurity has preserved a sense of quiet continuity. Here, ancient monastic architecture coexists with grazing fields, village paths, and the daily rhythms of Konkan life. To explore Kuda is to encounter rock-cut heritage not as a museum exhibit, but as part of an evolving rural landscape.

Geographical Setting and Landscape Context

The Kuda Caves are located in the Raigad district of Maharashtra, inland from the Konkan coastline and not far from the historic port region of Janjira. The caves are carved into a basalt hill rising gently above surrounding villages and agricultural land. Unlike dramatic escarpments or isolated cliffs, this hill blends seamlessly into the terrain, making the caves almost invisible until approached closely.

The broader landscape reflects classic Konkan geography: lateritic soil, undulating low hills, seasonal streams, and dense greenery during the monsoon. Coconut groves, rice fields, and patches of forest surround the site, reinforcing the impression that Kuda was never intended as a remote sanctuary, but rather as a contemplative space integrated into everyday movement and habitation.

Historical Overview of the Kuda Caves

Chronology and Patronage

The Kuda Caves date primarily to the early centuries of the Common Era, with most scholars placing their construction between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE. This period corresponds with the expansion of Buddhist monastic networks across western India, supported by trade routes linking inland regions with Konkan ports.

Inscriptions found at the site reference donors from mercantile communities, indicating that Kuda functioned as a monastic establishment supported by trade-linked patronage. The proximity of ancient coastal routes suggests that monks here may have interacted regularly with traders, travelers, and local populations rather than existing in isolation.

Buddhist Monastic Function

Architecturally, Kuda belongs to the early Buddhist rock-cut tradition, emphasizing functional spaces for residence, meditation, and communal gathering. The caves include viharas (monastic living quarters) and a chaitya (prayer hall), reflecting a complete monastic complex rather than a single-purpose excavation.

The simplicity of design is deliberate. Ornamentation is minimal, and attention is focused on proportion, light, and spatial clarity—qualities essential to monastic discipline and contemplative practice.

Architectural Features and Cave Layout

Viharas: Spaces of Residence

The majority of the caves at Kuda are viharas, consisting of rectangular halls with cells carved along the sides. These cells would have served as living and sleeping quarters for monks, offering protection from monsoon rain and summer heat.

Stone benches, door frames, and shallow niches remain visible, bearing the marks of hand tools and sustained use. The restrained design underscores the practical priorities of early Buddhist monastic life: shelter, discipline, and communal order.

The Chaitya Hall

The chaitya at Kuda represents the spiritual heart of the complex. Though smaller than the grand chaityas found at sites like Karla or Bhaja, it retains the essential elements of the form—an apsidal hall, a central stupa, and a vaulted ceiling carved to resemble wooden architecture.

Light enters the hall softly, illuminating the stupa without overwhelming the interior. This controlled illumination reflects an architectural understanding of atmosphere as an aid to ritual focus rather than visual spectacle.

Inscriptions and Social Insight

One of Kuda’s most valuable contributions to historical understanding lies in its inscriptions. Donative records carved into the rock provide names, occupations, and affiliations of those who supported the monastery. Merchants, craftsmen, and local patrons are all represented, offering a glimpse into the social fabric of the region during the early historic period.

These inscriptions reinforce the idea that Buddhist monasticism in the Konkan was deeply intertwined with commerce and travel. The caves functioned not only as spiritual centers but also as nodes within broader economic and cultural networks.

Kuda Caves in the Context of Konkan Trade Routes

The Konkan coast has long served as a corridor between inland India and maritime trade networks across the Arabian Sea. Ports such as Chaul and Janjira facilitated the movement of goods, ideas, and people. Monastic sites like Kuda benefited from this circulation, offering rest, instruction, and ritual space to travelers.

This relationship between monastic establishments and trade routes mirrors patterns seen elsewhere in India and beyond. Just as mangrove-lined waterways support movement and exchange in delta regions explored during a Sundarban Trip, the Konkan’s coastal and inland routes sustained interconnected systems of travel and belief.

Ecological Setting and Sensory Environment

The hill housing the Kuda Caves supports a modest but varied ecosystem. During the monsoon, the surroundings turn vividly green, with grasses, shrubs, and seasonal wildflowers covering the slopes. Insects, birds, and small reptiles are commonly observed, adding subtle movement and sound to the experience.

Outside the monsoon, the landscape becomes quieter and more subdued, with dry grasses and open views revealing the contours of the hill. This seasonal contrast enhances appreciation of how ancient builders adapted their architecture to climatic rhythms.

Best Time and Season to Visit

Post-Monsoon and Winter: October to February

The most comfortable period to visit Kuda Caves is from October through February. Temperatures are moderate, humidity is lower, and access paths are stable. Vegetation remains lush after the monsoon, creating a pleasant visual setting without the challenges of heavy rain.

This season is ideal for detailed exploration, photography, and unhurried observation of architectural features.

Monsoon: July to September

Visiting during the monsoon offers a dramatically different atmosphere. Mist, fresh greenery, and the sound of rain transform the caves into deeply atmospheric spaces. However, slippery paths and increased insect activity require caution.

Travelers accustomed to monsoon-dependent landscapes—such as coastal forests and river deltas visited through a Best Sundarban Tour Package—will recognize similar rewards and constraints here.

Ideal Travel Duration and Itinerary Planning

Kuda Caves can be explored thoroughly within half a day, but combining the visit with nearby villages, countryside walks, or other lesser-known Konkan sites makes a one- to two-day itinerary more fulfilling. This allows time to absorb the setting rather than treating the caves as a brief stop.

Slow pacing is essential. The site reveals its significance through detail and context rather than immediate impact.

Route and Accessibility

The caves are accessible by road from major Konkan towns such as Alibaug and Murud. The final approach involves village roads that pass through agricultural land and small settlements, reinforcing the sense of arrival into a lived landscape rather than a fenced monument.

Public transport options are limited for the last stretch, making private vehicles or local transport arrangements more practical. Clear signage is minimal, so prior navigation planning is advisable.

Key Highlights of the Kuda Caves

Spatial Coherence of the Complex

Unlike isolated cave shrines, Kuda presents a coherent ensemble of spaces designed for sustained habitation. Moving between viharas and the chaitya reveals how daily life and ritual practice were integrated.

Relative Isolation and Quiet

The low visitor numbers at Kuda contribute significantly to its appeal. Silence is not imposed but natural, allowing visitors to experience the caves in a manner closer to their original use.

Inscriptions as Human Connection

The donor inscriptions provide a direct link to individuals who lived and worked in the region nearly two millennia ago. Reading these names in situ adds a human dimension often missing from more crowded heritage sites.

Cultural Significance and Continuity

Although the Buddhist monastic community that once occupied Kuda has long since disappeared, the site continues to hold cultural relevance. Local awareness of the caves, informal care by villagers, and respectful use of the surrounding land contribute to their preservation.

This continuity reflects a broader Konkan pattern, where historical sites remain embedded within everyday landscapes rather than isolated from them.

Practical Insights for Responsible Visitors

Visitors should approach Kuda Caves with respect for both heritage and local life. Avoid touching inscriptions or carved surfaces, refrain from loud behavior, and carry back all waste.

Footwear with good grip is recommended, especially during or after the monsoon. There are no formal facilities at the site, reinforcing the need for preparation and self-sufficiency.

Kuda Caves as an Alternative Heritage Experience

Kuda represents a different mode of heritage travel—one that prioritizes understanding over consumption. The absence of crowds, ticket counters, and interpretive signage places responsibility on the visitor to engage thoughtfully.

For researchers, students, and reflective travelers, this lack of mediation is an advantage, allowing direct interaction with space, material, and context.

Quiet Stone, Enduring Meaning

The Kuda Caves stand as a testament to an era when spiritual life, trade, and landscape were closely interwoven. Their understated presence in the Konkan hills is not a sign of insignificance, but of resilience—having endured centuries without being overwritten by modern spectacle.

For those willing to look beyond marquee destinations, Kuda offers a deeply rewarding encounter with rock-cut heritage in its most unassuming form. It is a place where history speaks softly, and where attentive travel becomes an act of preservation.