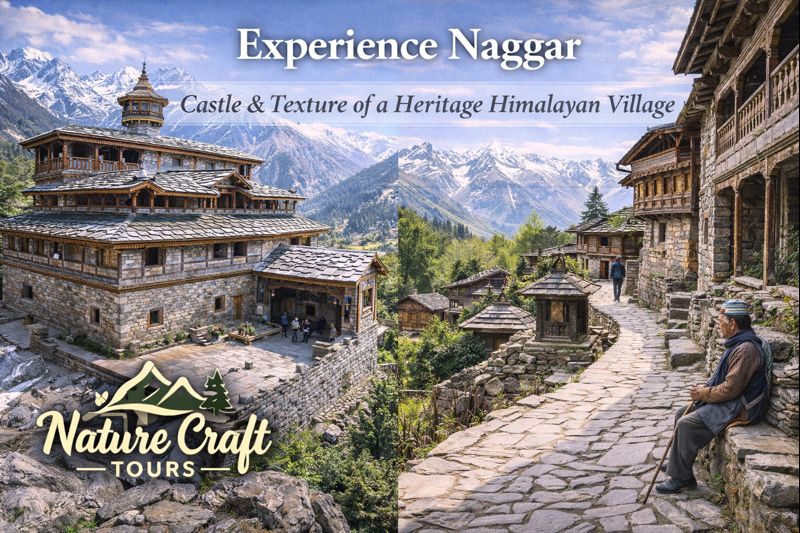

Naggar: Castle, Craft, and the Living Texture of a Himalayan Heritage Village

Perched quietly above the Beas Valley, away from the constant motion of Manali’s roads, Naggar unfolds as a place where history has not been sealed behind glass but continues to breathe through stone walls, wooden balconies, temple courtyards, and village lanes. Naggar is not merely a destination marked by a castle; it is a textured heritage settlement where architecture, landscape, and daily life remain deeply interwoven. The village does not present itself through spectacle. Instead, it reveals itself slowly—through proportion, material, silence, and continuity.

Once the capital of the former Kullu kingdom, Naggar retains an authority that is subtle rather than imposing. The castle crowns a rocky spur, but below it spreads a lived village fabric shaped by agriculture, craft, and ritual. This coexistence of royal legacy and everyday life makes Naggar distinct among Himalayan heritage sites. It is neither frozen in time nor overtaken by modernity. It exists in a careful middle ground.

This article explores Naggar as a heritage village rather than a single monument. It examines the castle as an anchor, the village as a living organism, and the surrounding landscape as the context that gives both meaning. Written from a field-based, observational perspective, the narrative prioritizes understanding over consumption and continuity over quick impressions.

Destination Overview: Situating Naggar in the Kullu Valley

Naggar is located approximately 20 kilometers from Manali, on the left bank of the Beas River, at an elevation of around 1,800 meters above sea level. Unlike settlements that hug the valley floor, Naggar occupies a raised terrace, granting it expansive views across orchards, river bends, and distant mountain ridges. This elevated position was strategic, offering both defense and climatic comfort.

Geographically, Naggar sits at a transition point—between the dense tourism zones of Manali and the quieter agricultural villages of the middle Kullu Valley. This position has allowed it to retain a relatively intact cultural landscape while remaining accessible.

The village unfolds in layers: the castle at the top, temples and heritage houses clustered around it, followed by terraced fields, orchards, and lower hamlets. Movement through Naggar is vertical as much as horizontal, reinforcing awareness of terrain and scale.

A Settlement Shaped by Governance and Geography

Naggar’s form reflects its historical role as a seat of power. Administrative needs, ritual spaces, and residential quarters were organized around proximity to the castle, while agricultural zones extended outward. This structure remains legible today, making Naggar an unusually readable historic settlement.

Naggar Castle: Stone, Wood, and Authority

Naggar Castle is the most visible symbol of the village’s past, yet its significance lies as much in how it was built as in what it represented. Constructed in the fifteenth century, the castle exemplifies traditional Kath-Kuni architecture—a seismic-resistant technique combining layers of stone and interlocking timber.

Kath-Kuni Architecture and Craft Knowledge

The castle’s walls alternate between dressed stone and horizontal wooden beams, a method that provides flexibility during earthquakes. This was not an aesthetic choice but a deeply practical one, rooted in generations of local knowledge. The same technique appears in temples and houses throughout the village, creating architectural continuity.

Balconies, carved doorways, and interior courtyards reflect a synthesis of functionality and restraint. Ornamentation is minimal, allowing proportion and material to speak.

The Castle as Cultural Anchor

While the castle once housed rulers, its presence today serves as a cultural anchor rather than a seat of authority. From its terraces, one can read the entire settlement below—the fields, roofs, paths, and river beyond—understanding how governance, land, and people were once visually and spatially connected.

Heritage Village Texture: Walking Through Naggar

Naggar’s greatest strength lies not in isolated landmarks but in the continuity of its village fabric. Walking through Naggar is an exercise in observation: textures shift subtly from stone to mud plaster, from slate roofs to wooden shingles, from cultivated fields to forest edges.

Village Lanes and Domestic Architecture

Narrow lanes wind between houses built close to one another, creating sheltered microclimates. Homes often feature projecting balconies, internal courtyards, and storage spaces integrated into living areas. These are not decorative choices but responses to climate, social structure, and material availability.

Agriculture and Orchard Life

Terraced fields and orchards surround the village, growing apples, vegetables, and grains. These working landscapes are integral to Naggar’s identity. Seasonal changes—blossoms in spring, harvest in autumn—define the village calendar as much as festivals do.

Cultural and Historical Significance

Naggar’s history is inseparable from the Kullu kingdom, which ruled large parts of the valley for centuries. As the former capital, Naggar hosted administrative, religious, and cultural functions that shaped regional identity.

Temple Traditions and Local Deities

Temples in and around Naggar reflect a decentralized religious system common to the Western Himalaya. Local deities are closely tied to specific villages and landscapes, reinforcing a sense of place-based spirituality.

Naggar and Cross-Cultural Exchange

In the twentieth century, Naggar became a quiet hub for artists and thinkers, drawn by its atmosphere and relative isolation. This layered history—royal, agrarian, artistic—adds depth to the village’s cultural texture.

Ecological Context: Village, Forest, and River

Naggar’s ecological setting contributes significantly to its character. The village sits between riverine ecosystems below and mixed Himalayan forests above, creating environmental diversity within short distances.

Forest Edges and Biodiversity

Forests above Naggar support deodar, pine, and broadleaf species, stabilizing slopes and regulating water flow. These forests also act as cultural boundaries, marking the transition from cultivated land to wilderness.

Beas Valley Relationship

From Naggar’s terraces, the Beas River is visible as a defining feature of the valley. While the village itself sits above flood levels, its agriculture depends on river-fed irrigation systems downstream.

Best Time and Season to Visit Naggar

Spring (March to May)

Spring brings orchard blossoms and moderate temperatures. This is an ideal season for walking through the village and observing agricultural activity.

Summer (June to September)

Summer remains pleasant due to elevation. Monsoon rains enhance greenery but may limit long walks during heavy showers.

Autumn (October to November)

Autumn offers clarity and harvest activity. Views across the valley are especially sharp during this season.

Winter (December to February)

Winters are quiet and cold, with occasional snowfall. This season suits travelers interested in stillness rather than movement.

Ideal Travel Duration

Naggar is often visited briefly, but its depth becomes apparent over time. A minimum of two full days is recommended.

Suggested Duration

- Day 1: Castle exploration and upper village walks

- Day 2: Lower village lanes, orchards, and forest edges

- Day 3 (optional): Slow observation and cultural spaces

Route and Accessibility

Naggar is accessed by road from Manali and other Kullu Valley towns. The approach climbs gently from the valley floor, offering expanding views.

Internal Movement

The village is best explored on foot. Walking reveals spatial relationships and textures that vehicles bypass.

Naggar in a Wider Geographic Perspective

Naggar’s heritage village model contrasts with other Indian landscapes shaped by entirely different forces. While Naggar evolved through mountain governance and agriculture, delta regions evolved through tides and mangroves.

Travelers who experience both Himalayan settlements like Naggar and lowland ecosystems explored on a Sundarban Trip often gain deeper insight into how geography produces distinct cultural forms.

Practical Insights for Travelers

Walking and Observation

Comfortable footwear is essential due to stone paths and uneven terrain. Slow walking enhances understanding.

Respecting Village Life

Naggar is a living village. Travelers should remain mindful of privacy, particularly near homes and temples.

Environmental Responsibility

Avoid littering, respect agricultural boundaries, and minimize noise. Heritage villages are sensitive to cumulative impact.

Integrating Naggar into Broader Travel Plans

Naggar pairs well with journeys that emphasize cultural and ecological diversity. Structured itineraries such as a Best Sundarban Tour Package illustrate how contrasting landscapes—mountains and deltas—offer complementary perspectives.

A Thoughtful Two-Day Plan for Naggar

Day One: Castle and Core Village

Explore the castle and upper settlement. Observe architectural details and village layout from elevated points.

Day Two: Orchards and Lower Hamlets

Walk through lower lanes and agricultural zones. Spend time observing daily routines.

Naggar as a Living Heritage Landscape

Naggar is not defined by a single monument or moment in history. It is defined by continuity—of craft, settlement, and relationship with land. The castle anchors memory, but the village sustains life.

For travelers willing to slow down, Naggar offers something increasingly rare: a heritage landscape that remains lived-in, legible, and resilient. It reminds us that history is not only preserved—it is practiced daily, in stone, wood, field, and path.