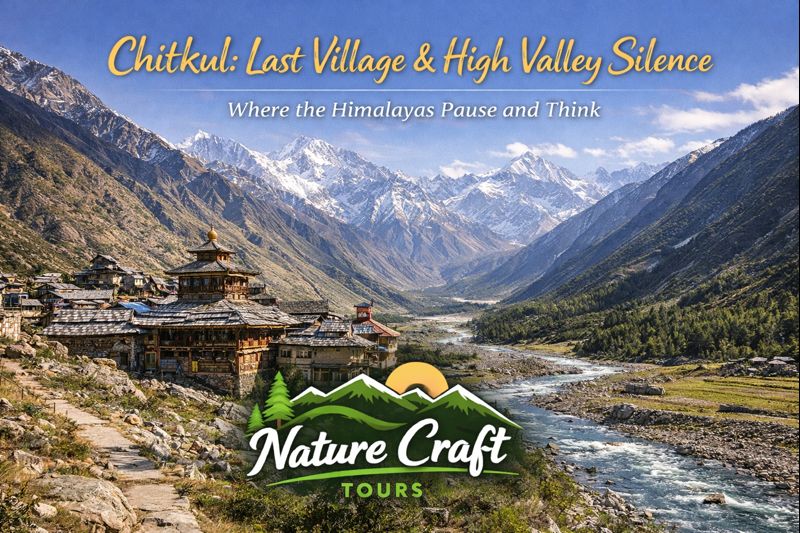

Chitkul: The Last Village Mood and the Silence of a High Himalayan Valley

Chitkul is not defined by what it offers, but by what it withholds. Located at the far end of a narrowing Himalayan corridor, this village exists where roads hesitate, seasons dictate authority, and silence becomes a tangible presence. Often referred to as the last inhabited village on the Indo-Tibetan frontier side of Himachal Pradesh, Chitkul is less a destination and more a psychological threshold. Beyond it lie higher valleys, harsher climates, and geopolitical boundaries; within it resides a way of life shaped by altitude, isolation, and restraint.

The “Last Village Mood” of Chitkul is not symbolic—it is structural. Everything here feels terminal in a geographical sense: the road ends, the valley opens, the river widens its voice, and human settlement thins into necessity rather than choice. The “High Valley Silence” is not the absence of sound, but the dominance of natural acoustics—wind across grass, the Baspa River striking stones, distant bells from livestock, and long intervals without mechanical interruption. This silence recalibrates perception. Time stretches. Observation deepens.

This travel narrative approaches Chitkul as a lived high-altitude settlement rather than a scenic endpoint. It examines how geography enforces lifestyle, how culture survives isolation, and how travelers can engage with such a place without disrupting its fragile equilibrium. Chitkul is not meant to be consumed quickly. It demands stillness, respect, and the willingness to let the valley set the terms of engagement.

Destination Overview: Chitkul in the High Baspa Valley

Geographical Location and Elevation

Chitkul lies in the upper reaches of the Baspa Valley in the Kinnaur district of Himachal Pradesh, at an elevation of approximately 3,450 meters above sea level. It is the final permanent settlement along the Baspa River before the terrain transitions into higher alpine zones and restricted border regions. The village is framed by steep slopes, open grazing grounds, and distant snowfields that remain visible for much of the year.

Unlike lower Himalayan towns that expand laterally, Chitkul is spatially contained. Its geography permits little excess. Fields, houses, temples, and paths are tightly integrated, reflecting a settlement model optimized for survival rather than growth. The valley floor is narrow, and every usable patch of land has been shaped carefully over generations.

Climate and Environmental Conditions

Chitkul experiences a harsh alpine climate. Summers are short and cool, with strong sunlight during the day and sharp temperature drops after sunset. Winters are long, severe, and isolating, with heavy snowfall cutting off road access for months. These conditions define not only travel feasibility but also the cultural calendar and architectural form.

The Baspa River, glacial-fed and fast-moving, moderates certain microclimatic effects, preventing extreme dryness during the warmer months. However, the overall environment remains demanding, reinforcing a lifestyle built around preparation, storage, and seasonal migration.

The Meaning of “Last Village”: Geography, Psychology, and Reality

Beyond Infrastructure and Connectivity

Chitkul’s identity as the last village is not a tourism slogan; it is an infrastructural truth. The motorable road ends here. Beyond Chitkul, movement is restricted by terrain, climate, and policy. This terminal position influences behavior—both for residents and visitors. Supplies are planned carefully. Movement follows seasonal windows. There is little tolerance for excess.

This end-of-the-road geography creates a psychological quietness. There is no onward rush, no passing traffic. People who arrive here either stay briefly or linger intentionally. The absence of transit traffic reinforces the sense that Chitkul exists for itself, not as a conduit.

Silence as an Environmental Condition

Silence in Chitkul is not emptiness. It is layered. During the day, it is broken by river flow, animal movement, and occasional human voices. At night, it deepens into a vast acoustic stillness punctuated only by wind and distant water. This silence can feel unfamiliar to those accustomed to constant ambient noise, but over time it becomes grounding.

High valley silence sharpens awareness. Travelers often report heightened sensitivity to light, temperature, and sound. This sensory recalibration is part of Chitkul’s experiential value.

Village Texture: Architecture and Settlement Pattern

Traditional Wooden Houses

Chitkul’s houses follow the Kinnauri architectural tradition, characterized by interlocking wooden beams, stone masonry, and slate roofs. This construction method provides thermal insulation, flexibility during seismic activity, and resistance to heavy snow loads. The use of local materials ensures harmony with the surrounding landscape.

Homes are compact, multi-level structures. Lower levels often store fodder or house livestock, while upper floors serve as living spaces. Windows are small to retain heat, and balconies face the valley to capture maximum sunlight during short summers.

Spatial Organization and Community Living

The village is arranged in close clusters, minimizing exposure to wind and cold. Narrow paths connect houses, temples, and fields. Open spaces are functional rather than ornamental—used for drying crops, grazing animals, or communal gatherings.

This compactness reinforces social cohesion. In Chitkul, community is not optional; it is essential for survival during long winters and periods of isolation.

Cultural and Historical Context

Kinnauri Identity and Belief Systems

Chitkul is part of the broader Kinnauri cultural region, known for its syncretic belief systems that blend Hindu, Buddhist, and animistic traditions. Village deities play a central role in governance, agricultural decisions, and festival timing. Spiritual authority here is local and deeply embedded in landscape.

Rituals are not staged events; they are integrated into seasonal cycles. Masks, music, and processions appear during specific times of year, often tied to agricultural milestones or climatic transitions.

Historical Isolation and Borderland Context

Historically, Chitkul’s location near ancient trade and migration routes connected it indirectly to trans-Himalayan networks. However, modern geopolitical boundaries transformed it into a borderland settlement with restricted outward movement. This shift increased isolation but also preserved cultural practices by limiting external influence.

The Baspa River and the High Valley Landscape

River as Lifeline

The Baspa River flows just below Chitkul, its cold, clear waters fed by snowmelt from surrounding peaks. The river supports irrigation, grazing grounds, and ecological diversity. It also shapes the valley’s soundscape, providing a constant auditory presence that contrasts with the otherwise quiet environment.

Riverbanks are treated with respect. Local customs discourage pollution or careless use, reflecting an understanding of the river’s importance in a fragile high-altitude ecosystem.

High Meadows and Grazing Grounds

Above the village lie open meadows used for seasonal grazing. These alpine pastures are accessible only during summer months and play a crucial role in sustaining livestock. The movement of animals to and from these meadows follows traditional patterns refined over generations.

Best Time and Season to Visit Chitkul

Late Spring to Early Summer (May to June)

Road access resumes as snow recedes. The valley awakens gradually, with fresh grass, blooming wildflowers, and increasing agricultural activity. Temperatures are cool but manageable, making this an ideal period for first-time visitors.

Peak Summer (July to September)

This is the most accessible and active season. Days are long, fields are cultivated, and village life is fully visible. Occasional rainfall enhances greenery without overwhelming the terrain. High valley silence remains intact despite increased movement.

Autumn (October)

Harvest season brings visual richness and cultural activity. Temperatures drop quickly, and preparations for winter dominate daily routines. This is a rewarding time for travelers interested in observing seasonal transition.

Winter (November to April)

Heavy snowfall isolates Chitkul. Travel during this period is generally not feasible. However, winter defines the village’s rhythm and explains many aspects of its architecture and culture.

Ideal Travel Duration and Pace

Chitkul is not suited to brief stops. A minimum of two nights allows acclimatization and meaningful engagement. A three- to four-day stay enables slow walks, river observation, and participation in daily rhythms without intrusion.

The village rewards stillness. Repeating the same path at different times of day reveals subtle changes in light, sound, and activity that define the high valley mood.

Route and Accessibility

Approach to Chitkul

Chitkul is reached via a mountain road that ascends along the Baspa Valley. The journey involves steep gradients, narrow sections, and changing weather conditions. Travel times are longer than distances suggest, reinforcing the need for careful planning.

As with other landscape-driven journeys in India—whether entering a high Himalayan valley or navigating tidal forests during a Sundarban Trip—the approach itself shapes expectations and mindset.

Movement Within the Village

Chitkul is best explored entirely on foot. The village is compact, and walking allows respectful engagement with people and environment. Vehicular movement should be minimized to preserve silence and safety.

Key Attractions and Experiences

Village Walks and Riverbanks

Simple walks through the village and along the Baspa River offer the most authentic experience. Observing daily routines—field work, animal care, communal gatherings—provides insight into high-altitude living.

Temples and Sacred Spaces

Local temples reflect Kinnauri spiritual traditions. These spaces are active and should be approached with respect. Observing rituals quietly is often more meaningful than participation.

High Valley Views

Open viewpoints around the village reveal the scale of the surrounding mountains and the narrowing valley. These perspectives reinforce Chitkul’s position as a terminal settlement.

Ecological Sensitivity and Responsibility

Chitkul exists within a fragile alpine ecosystem. Soil regeneration is slow, water sources are limited, and waste management is challenging. Responsible travel behavior is essential to prevent long-term damage.

Visitors should avoid single-use plastics, respect grazing areas, and follow local guidelines regarding movement and resource use.

Practical Insights for Travelers

Health and Acclimatization

Due to high altitude, gradual acclimatization is important. Travelers should avoid overexertion on arrival, stay hydrated, and monitor physical responses to altitude.

Cultural Sensitivity

Chitkul is a living village, not an exhibit. Photography should be discreet and only with permission. Dress modestly, especially near religious spaces.

Packing and Preparation

Layered clothing is essential year-round. Even summer nights are cold. Sturdy footwear is recommended for uneven paths and variable terrain.

Chitkul in the Broader Context of Slow and Nature-Led Travel

Chitkul represents a form of travel where environment dictates behavior. Its appeal aligns with other ecosystems where silence, restraint, and continuity shape experience. Travelers who value such depth often appreciate carefully structured, low-impact journeys similar in philosophy to experiences like the Best Sundarban Tour Package, where landscape and culture define pace.

Chitkul as an End Point and a Beginning

Chitkul is an end point in geography but a beginning in perception. Its last village mood strips away excess and foregrounds essentials—water, shelter, community, and time. The high valley silence is not emptiness; it is presence without distraction.

For travelers willing to slow down and listen, Chitkul offers a rare Himalayan experience rooted in authenticity rather than display. It stands quietly at the edge of the inhabited world, not asking to be discovered, but waiting to be understood.