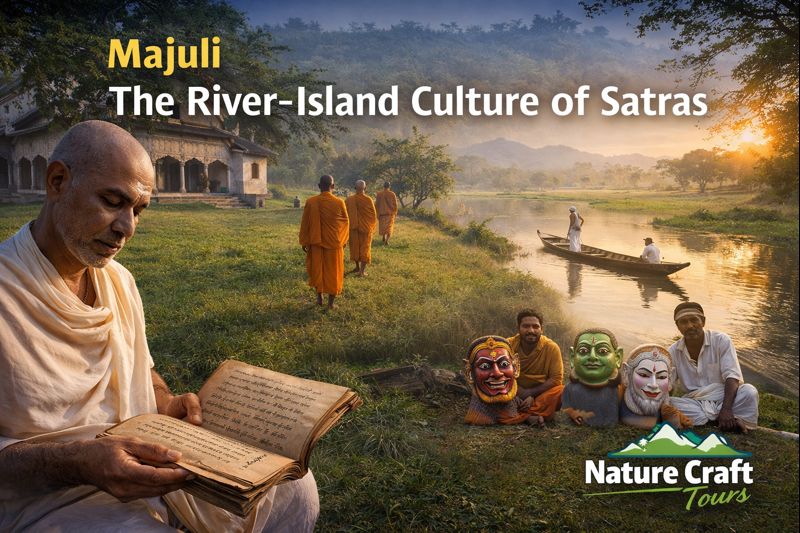

Majuli: The River-Island Culture of Satras

Majuli is not merely a geographical phenomenon formed by the restless flow of the Brahmaputra; it is a living, breathing cultural archive shaped by faith, art, resilience, and riverine ecology. To arrive in Majuli is to enter a landscape where water determines rhythm, monasteries shape daily life, and centuries-old traditions continue not as museum artifacts but as lived reality. The island’s true identity reveals itself not through spectacle, but through patience—through conversations with monks, observation of ritual practices, and long walks along embankments where erosion and devotion coexist. This is the river-island culture of Satras, and Majuli is its quiet yet profound epicenter.

Understanding Majuli: Geography, Scale, and Setting

Located in the upper reaches of Assam, : Majuli is widely recognized as one of the world’s largest inhabited river islands. Formed by the Brahmaputra River and its subsidiary channels, Majuli once covered a significantly larger area than it does today. Continuous erosion and flooding have reduced its landmass over decades, yet what remains is a uniquely fertile, culturally dense landscape that has retained its spiritual core despite environmental vulnerability.

Majuli’s terrain is predominantly flat, interspersed with wetlands, seasonal streams, paddy fields, and clusters of villages. The soil, renewed annually by flood-borne silt, supports rice cultivation, mustard fields, and vegetable farming. The island’s isolation—cut off from the mainland except by ferries—has historically limited large-scale urbanization, allowing indigenous culture and monastic traditions to evolve with minimal external interference.

The Satras of Majuli: Foundations of a Cultural Ecosystem

Origins of the Satra Institution

The defining feature of Majuli’s cultural identity lies in its Satras—Vaishnavite monasteries established in the 15th and 16th centuries under the reformist saint-scholar Srimanta Sankardeva and his disciples. These institutions were conceived not merely as places of worship but as centers for ethical living, artistic expression, social reform, and community education. The Satra system introduced a form of egalitarian spiritual practice that emphasized devotion, discipline, and cultural unity.

Each Satra operates as a self-contained cultural unit, traditionally governed by a head monk and sustained by resident bhakats (monks or disciples). Their daily routines blend prayer, artistic practice, scriptural study, and agricultural labor, creating a holistic rhythm of life that integrates the sacred and the practical.

Major Satras and Their Distinct Identities

Majuli is home to several historically significant Satras, each with its own philosophical emphasis and artistic legacy. Auniati Satra is known for its preserved manuscripts and ceremonial grandeur, while Kamalabari Satra has long served as a hub for classical dance and scholarly discourse. Dakhinpat Satra retains strong ritual traditions and seasonal festivals, whereas Samaguri Satra is internationally recognized for its handcrafted masks used in religious theater.

These Satras are not uniform institutions; they represent diverse interpretations of Vaishnavism, coexisting within a shared spiritual framework. Visiting them reveals variations in architecture, ritual practice, and community engagement, offering insight into how belief systems adapt across generations.

Majuli as a Living Museum of Performing Arts

Sattriya Dance: Ritual Movement as Cultural Memory

One of Majuli’s most significant contributions to Indian classical arts is Sattriya dance, which originated within the Satras as a medium for spiritual storytelling. Unlike stage-oriented classical forms, Sattriya evolved as a ritual practice, performed during religious observances and festivals. Its movements are restrained yet expressive, emphasizing devotion over spectacle.

Training in Sattriya is rigorous and traditionally begins at a young age within monastic settings. The dance draws upon ancient texts, rhythmic syllables, and mythological narratives, serving as a bridge between theology and aesthetics. Observing a Sattriya performance within a Satra courtyard offers an experience that is both meditative and culturally immersive.

Ankiya Naat and Mask Traditions

Ankiya Naat, a form of one-act devotional drama introduced by Sankardeva, remains an integral part of Majuli’s cultural calendar. These performances combine dialogue, music, dance, and elaborate masks to convey moral and spiritual themes. The masks, traditionally crafted from bamboo, clay, and natural pigments, are functional art forms rather than decorative objects.

Samaguri Satra’s mask-making tradition exemplifies how artisanal knowledge is transmitted across generations. Each mask reflects symbolic character traits, and the process of creation is deeply intertwined with ritual observance, reinforcing the inseparability of art and faith in Majuli.

Ecological Context: Living with the Brahmaputra

Majuli’s culture cannot be understood without acknowledging its ecological reality. The Brahmaputra is both benefactor and adversary, nourishing the island’s agriculture while steadily eroding its edges. Seasonal flooding is a normalized aspect of life, shaping housing styles, crop cycles, and mobility patterns.

Wetlands surrounding Majuli serve as habitats for migratory birds, native fish species, and aquatic vegetation. Traditional fishing practices, largely sustainable and community-based, reflect long-standing ecological knowledge. However, climate variability and upstream interventions have increased environmental pressures, making Majuli a critical case study in human adaptation to riverine change.

Planning a Journey to Majuli

Best Time and Season to Visit

The most suitable period to explore Majuli is between October and March, when water levels stabilize and weather conditions remain moderate. Post-monsoon months bring clear skies and accessible ferry routes, while winter mornings offer mist-laden landscapes that enhance the island’s contemplative atmosphere. Summer and monsoon seasons, though agriculturally significant, present logistical challenges due to flooding and erosion.

Ideal Travel Duration

A meaningful visit to Majuli requires a minimum of two to three days. This allows sufficient time to explore multiple Satras, engage with local communities, observe artistic practices, and experience the island’s ecological rhythms. Shorter visits risk reducing Majuli to a checklist destination rather than an immersive cultural experience.

Route and Accessibility

Majuli is accessed primarily via ferry from the town of Jorhat, which is well-connected by road and air to major cities in Assam. Ferry crossings across the Brahmaputra are an essential part of the journey, offering perspectives on the river’s vastness and the logistical realities of island life. Seasonal variations may affect schedules, and travelers should approach the journey with flexibility and patience.

Key Attractions and Experiences

Beyond the Satras, Majuli offers a series of understated yet enriching experiences. Village walks reveal traditional stilted houses, handloom weaving, and agrarian routines. Pottery clusters demonstrate techniques that rely on natural clay and minimal mechanization. Riverside embankments provide vantage points to observe erosion patterns and daily river traffic.

Festivals such as Raas Leela transform the island into a cultural gathering space, drawing participants from across Assam. These events are not staged for tourism but emerge organically from religious calendars, allowing visitors to witness collective devotion rather than curated performance.

Practical Insights for Thoughtful Travelers

Travelers to Majuli should approach the destination with cultural sensitivity and environmental awareness. Photography within Satras often requires permission, particularly during rituals. Modest attire is advisable, and interactions with monks should be respectful and unhurried.

Infrastructure on the island remains basic, and power or connectivity interruptions are common. Rather than viewing this as inconvenience, it is helpful to see such conditions as integral to understanding Majuli’s rhythm of life. Supporting local artisans and services contributes directly to the island’s economic resilience.

Majuli in the Larger Context of Riverine Cultures

Majuli’s story resonates beyond Assam, offering parallels to other deltaic and river-based cultures in South Asia. Just as the mangrove landscapes of the Sundarbans represent a delicate balance between human settlement and tidal ecology, explored in journeys such as a Sundarban Tour, Majuli illustrates how spiritual institutions can anchor communities amid environmental uncertainty.

For travelers seeking to understand India’s diverse cultural geographies, Majuli complements explorations of other riverine regions, including itineraries like a Sundarban Tour Package from Kolkata, by offering a contrasting yet thematically linked narrative of faith, ecology, and adaptation.

The Enduring Quiet of Majuli

Majuli does not announce itself through grandeur or convenience. Its significance unfolds gradually, through lived traditions, disciplined monastic life, and the ceaseless dialogue between land and river. The Satras stand not as relics of a bygone era but as functioning cultural systems that continue to guide ethical and artistic life on the island.

To journey through Majuli is to witness how culture can endure even as geography shifts beneath it. It is an experience that rewards attentiveness, humility, and time—qualities increasingly rare in contemporary travel. In the quiet courtyards of the Satras and along the eroding banks of the Brahmaputra, Majuli offers a lesson in continuity, reminding visitors that true heritage lives not in monuments, but in daily practice.