Mangalajodi (Near Chilika)

— Community-Based Birding Culture

Mangalajodi is not simply a birdwatching destination; it is a living example of how conservation, livelihood, and local identity can evolve together. Situated on the northern fringe of Chilika Lake, this small village has transformed its relationship with wetlands and wildlife through collective effort, patience, and self-realization. What makes Mangalajodi remarkable is not only the abundance of migratory birds that arrive each winter, but the human story behind their protection.

Once associated with intensive bird hunting, Mangalajodi today stands as one of India’s most respected models of community-led conservation. The wetlands here are calm, shallow, and expansive, offering ideal conditions for waterfowl, while the villagers themselves have become guides, guardians, and interpreters of the ecosystem. To visit Mangalajodi is to witness conservation not as an abstract policy, but as a lived, daily practice rooted in local culture.

Geographical Setting: Northern Chilika Wetlands

Mangalajodi lies near the northern edge of Chilika Lake, close to the foothills of the Eastern Ghats. Unlike the open lagoon sectors closer to the sea mouth, this part of Chilika is dominated by freshwater inflow, shallow marshes, and reed-filled wetlands. Seasonal streams and channels feed the area, creating a mosaic of open water, mudflats, and emergent vegetation.

The shallow depth of these wetlands is critical. It allows aquatic plants, plankton, and invertebrates to thrive, forming a rich food base for birds. The calm waters also make the area suitable for non-motorized boats, which play an important role in low-impact birding.

From Hunting Ground to Conservation Landscape

The history of Mangalajodi is central to its present identity. For decades, the wetlands were known as a hub for bird trapping, particularly during the winter migration season. Birds were hunted both for consumption and trade, driven by limited livelihood options and lack of awareness about ecological value.

The turning point came through sustained engagement by conservation groups, forest authorities, and local leaders, who worked with villagers rather than against them. Gradually, hunting was replaced by protection, and birdwatching emerged as an alternative source of income.

This transition was neither quick nor easy. It required trust-building, skill development, and a fundamental shift in how the community perceived the wetlands—not as a resource to be exploited, but as an asset to be preserved.

Community-Based Birding: How It Works

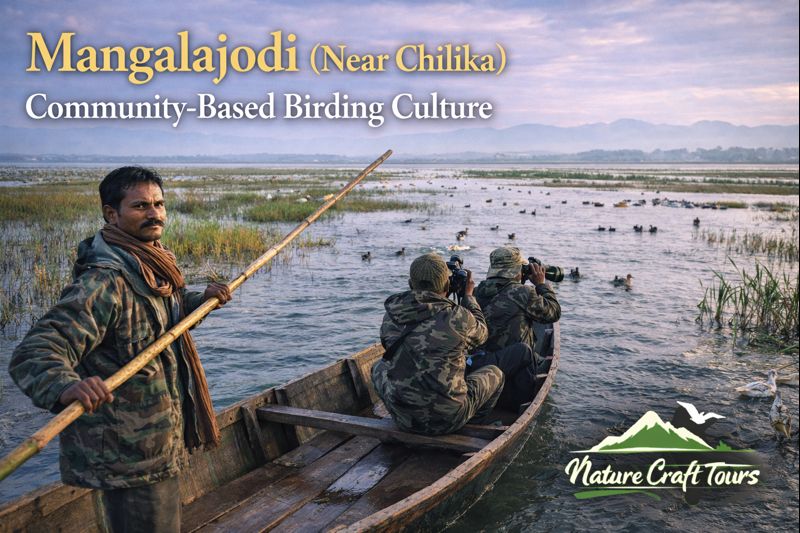

Birding at Mangalajodi is inseparable from community participation. Local residents operate traditional wooden boats, guide visitors through narrow channels, and interpret bird behavior based on years of lived experience. Many guides are former hunters who now use their deep knowledge of bird movement to protect rather than pursue.

Boat rides are slow and deliberate. Oars are preferred over motors to avoid noise and disturbance. This pace allows birds to continue feeding and resting, often at close range, creating an immersive yet respectful viewing experience.

Income from tourism is shared within the community, supporting households and reinforcing the value of conservation. This economic linkage ensures that protecting birds directly benefits those who live alongside them.

Seasonal Birdlife and Migration Patterns

Mangalajodi comes alive during the winter months, when migratory birds arrive from northern Asia, Central Asia, and parts of Europe. From November to February, the wetlands host thousands of waterfowl, shorebirds, and raptors.

Large congregations of ducks and geese dominate open water zones, while waders forage along mudflats. Reed beds provide shelter for smaller species and nesting sites for resident birds. The density and proximity of birds make Mangalajodi especially rewarding for observation.

As temperatures rise toward March, migratory populations gradually decline. By summer, the wetlands enter a quieter phase, dominated by resident species adapted to warmer conditions.

Ecological Significance of the Wetland System

Mangalajodi functions as an important buffer and feeding ground within the larger Chilika ecosystem. Its freshwater-dominated wetlands complement the brackish zones of the lagoon, increasing overall biodiversity.

The area supports complex food webs, from microscopic plankton to large waterbirds. By hosting large bird populations, the wetlands contribute to nutrient cycling and ecological balance. Birds play a role in controlling insect populations and dispersing plant material across the wetland.

This ecological productivity explains why Mangalajodi became such a critical stopover point along migratory routes.

The Birding Experience: Intimacy and Stillness

Birding in Mangalajodi is characterized by intimacy rather than spectacle. Boats glide quietly through narrow channels, often bringing observers within short distances of feeding birds. The absence of engine noise allows natural sounds—wingbeats, calls, and water movement—to dominate.

Early mornings are particularly rewarding. Mist often hangs low over the wetlands, softening light and enhancing visibility of bird silhouettes. As the sun rises, activity increases, offering dynamic scenes of feeding and flight.

For travelers familiar with wildlife experiences in tidal mangrove systems—such as those encountered during a Sundarban Tour—Mangalajodi presents a contrasting rhythm. Here, there are no strong currents or tides, only still water and patient observation.

Cultural Identity and Local Pride

The transformation of Mangalajodi has reshaped local identity. Conservation is now a source of pride rather than restriction. Villagers speak openly about the change, often emphasizing how protecting birds has brought stability, recognition, and dignity.

Children grow up seeing birds as valuable visitors rather than targets. This generational shift is perhaps the most significant outcome of the community-based approach.

Daily life in the village continues alongside tourism. Fishing, agriculture, and household routines coexist with guiding activities, reinforcing the idea that conservation need not replace traditional livelihoods, but can complement them.

Key Highlights for Visitors

The primary highlight of Mangalajodi is its boat-based birding, but the experience extends beyond species lists. Observing how guides navigate channels, read bird behavior, and adjust routes based on conditions provides insight into local knowledge systems.

Seasonal changes add variety. In peak winter, bird density is overwhelming. In early spring, departing flocks create dramatic flight scenes. Even quieter periods offer opportunities to understand wetland dynamics and resident bird behavior.

Best Time and Season to Visit

Optimal Birding Window

The best time to visit Mangalajodi is from November to February, when migratory birds are most abundant. December and January offer peak diversity and favorable weather conditions.

October may see early arrivals, while March marks gradual departure. Monsoon months are unsuitable for birding due to flooding and limited access.

Ideal Travel Duration

A single morning is sufficient for a focused birding experience, but spending one full day allows visitors to observe the wetlands under different light conditions. An overnight stay nearby enables early-morning access, which is critical for optimal viewing.

Those with deeper interest may combine Mangalajodi with other Chilika sectors to gain a broader understanding of lagoon ecology.

Route and Accessibility

Mangalajodi is easily accessible by road from Bhubaneswar, making it suitable for short trips as well as longer itineraries. The final approach passes through rural landscapes, offering a gradual transition from urban to wetland environment.

Access to the birding area is controlled by the local community, ensuring regulated entry and minimal disturbance.

Practical Insights for Responsible Travel

Visitors should follow the guidance of local boatmen, maintain silence during birding, and avoid sudden movements. Binoculars are essential, while photography should be undertaken respectfully.

Bright clothing and loud conversation detract from the experience and disturb wildlife. Supporting local guides directly contributes to the sustainability of the conservation model.

Mangalajodi in the Broader Wetland Context

India’s wetlands support diverse conservation approaches, from strictly protected reserves to community-managed landscapes. Mangalajodi represents the latter, demonstrating how local stewardship can be highly effective.

When compared with large-scale mangrove ecosystems explored through experiences like a Sundarban Tour Package, Mangalajodi highlights the value of small-scale, people-driven conservation within a larger ecological network.

Both models emphasize coexistence, though expressed through different landscapes and social structures.

Mangalajodi as a Living Conservation Model

Mangalajodi’s significance lies not only in the birds it hosts, but in the choices its community has made. The wetlands are protected because people decided they mattered—not just to nature, but to their own future.

For travelers, the experience offers more than bird sightings. It provides a lesson in how conservation can succeed when local knowledge, economic incentive, and ecological understanding align. Mangalajodi stands as a quiet yet powerful reminder that meaningful change often begins at the community level, shaped by patience, trust, and shared responsibility.