Sualkuchi — Where the Brahmaputra Spins Silk and Memory Weaves Identity

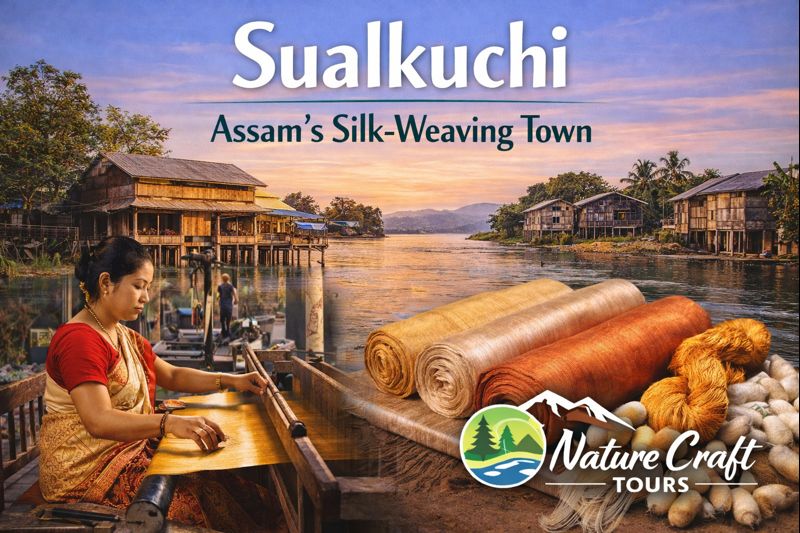

On the northern bank of the Brahmaputra, just beyond the expanding edges of Guwahati, lies Sualkuchi—a town where time does not rush, but flows steadily like the river beside it. Known across India as Assam’s silk-weaving town, Sualkuchi is not defined by monuments or dramatic landscapes. Its significance lies in continuity: the uninterrupted rhythm of looms, the inherited skill of hands, and the quiet dignity of a craft that has shaped Assamese identity for centuries.

To arrive in Sualkuchi as an explorer is to step into a living workshop rather than a tourist destination. Here, silk is not a product alone; it is language, livelihood, ritual, and social structure woven together. This article presents a deep, research-based exploration of Sualkuchi—its history, geography, weaving traditions, cultural landscape, and a thoughtfully structured tour plan for those who seek understanding rather than spectacle.

Geographical Setting: A Town Shaped by the Brahmaputra

Sualkuchi is situated approximately 35 kilometres west of Guwahati, along the fertile plains formed by the Brahmaputra River. The town’s location is not incidental. The river provides not only water and transport routes but also the environmental conditions necessary for sericulture—mulberry growth, silkworm rearing, and dye preparation.

The landscape here is flat and expansive, marked by clusters of traditional Assamese houses, narrow lanes, and open courtyards where looms are placed. Unlike industrial textile hubs, Sualkuchi’s production units are domestic, integrated into everyday life. This spatial intimacy between home and craft defines the town’s social fabric.

Why Sualkuchi Became a Weaving Centre

Historical records and oral traditions suggest that royal patronage during the Ahom period elevated Sualkuchi into a specialised weaving settlement. Skilled weavers were encouraged to settle here, and over generations, weaving knowledge became hereditary. The Brahmaputra ensured access to raw materials and facilitated trade, anchoring Sualkuchi within wider economic networks.

Historical Evolution of Silk Weaving in Sualkuchi

The history of Sualkuchi is inseparable from the history of Assamese silk. For centuries, silk cloth woven here adorned royalty, featured in religious rituals, and marked life-cycle ceremonies. Unlike many craft traditions disrupted by industrialisation, Sualkuchi adapted while retaining its core techniques.

Colonial encounters introduced new market pressures, but domestic weaving structures survived due to strong cultural attachment to handloom textiles. Post-independence, Sualkuchi emerged as a symbol of indigenous craftsmanship resisting homogenisation.

Continuity Through Change

Modern challenges—synthetic fabrics, mechanisation, and fluctuating demand—have reshaped production cycles. Yet, the essential character of Sualkuchi remains intact: hand-operated looms, family-based labour, and deep respect for material authenticity.

The Three Silks of Assam: Sualkuchi’s Core Identity

Muga Silk: The Golden Fibre

Muga silk is endemic to Assam and globally rare. Its natural golden hue intensifies with age, making it culturally symbolic of prosperity and continuity. Sualkuchi is one of the principal centres where Muga yarn is woven into mekhela chadors, sarees, and ceremonial fabrics.

Eri Silk: The Silk of Compassion

Eri silk, often referred to as peace silk, is produced without killing the silkworm. Its texture is warm and durable, traditionally associated with everyday wear and monastic use. Sualkuchi weavers have preserved Eri weaving techniques that prioritise comfort over sheen.

Pat Silk: Elegance and Ritual

Pat silk is known for its bright white base and smooth texture. Often used in formal and ritual contexts, Pat silk textiles from Sualkuchi reflect refined weaving precision and symbolic motifs.

The Loom as a Cultural Institution

In Sualkuchi, the loom is not an isolated machine; it is a cultural institution. Placed within courtyards or semi-open rooms, looms shape daily routines. Weaving schedules align with daylight, seasons, and household responsibilities.

Women play a central role in weaving, while men often manage yarn preparation, dyeing, and marketing. This division of labour sustains a balanced household economy deeply rooted in tradition.

Motifs, Patterns, and Meaning

Traditional motifs—flora, fauna, geometric forms—are not decorative alone. They encode regional identity, ecological awareness, and ritual symbolism. Each pattern carries lineage, often traceable to specific families or neighbourhoods.

Walking Through Sualkuchi: An Experiential Landscape

Exploring Sualkuchi is best done on foot. Narrow lanes reveal houses where looms operate visibly, inviting observation without exhibition. The absence of formal showrooms reinforces authenticity; weaving here is lived, not performed.

Sound becomes a guide—the steady rhythm of wooden looms creates an acoustic identity unique to the town. This sonic continuity underscores the town’s collective discipline.

Best Time to Visit Sualkuchi

October to March: Ideal Exploration Season

Cool, dry weather allows comfortable walking and extended interaction with weavers. Production activity is high, making this the best period for observation.

April to May: Pre-Monsoon Intensity

Though warmer, this season offers insight into dyeing and yarn preparation before the monsoon disrupts river transport.

Monsoon Months: Restricted but Revealing

Heavy rains slow production and access, yet they reveal the town’s resilience and its dependence on river rhythms.

Suggested 2-Day Sualkuchi Cultural Tour Plan

Day 1: Arrival and Weaving Immersion

Arrive from Guwahati in the morning. Walk through residential weaving lanes, observing loom operations. Engage in conversations to understand processes rather than purchasing immediately.

Day 2: Silk Understanding and River Context

Focus on silk varieties, yarn preparation, and design differences. End the day by visiting the Brahmaputra riverbank to understand how geography sustains the craft economy.

Sualkuchi in the Broader Craft Landscape of India

India’s handloom heritage is regionally diverse, yet Sualkuchi stands apart due to its silk specialisation and continuity of domestic production. Unlike large craft clusters oriented toward tourism, Sualkuchi remains primarily producer-focused.

Travellers familiar with ecosystem-driven cultures—such as those experienced during a Sundarban Tour—will recognise a similar interdependence between environment, livelihood, and identity.

Likewise, visitors undertaking immersive journeys like a Sundarban Tour Package from Kolkata may view Sualkuchi as a textile counterpart to ecological heritage landscapes.

Responsible Engagement with Weaving Communities

Visitors should approach Sualkuchi with sensitivity. Photography should be requested politely, conversations should respect working rhythms, and purchases should prioritise fair compensation over bargaining.

The survival of Sualkuchi’s weaving tradition depends not on admiration alone, but on ethical engagement.

Challenges and the Future of Sualkuchi

Market fluctuations, youth migration, and competition from power looms present ongoing challenges. However, renewed interest in sustainable textiles and indigenous craftsmanship offers cautious optimism.

Educational initiatives and cultural tourism—when handled responsibly—can strengthen rather than dilute Sualkuchi’s identity.

A Town That Weaves Time

Sualkuchi does not announce itself loudly. Its strength lies in repetition—the repeated movement of shuttles, the repeated patterns passed across generations, and the repeated choice to continue weaving despite uncertainty.

For the explorer, Sualkuchi offers a rare experience: witnessing culture not as performance, but as labour infused with meaning. Here, silk is not merely woven; time itself is threaded carefully through every loom.

As the Brahmaputra flows quietly beside the town and looms continue their measured rhythm, Sualkuchi stands as a testament to the endurance of craft, memory, and identity—woven patiently, one thread at a time.