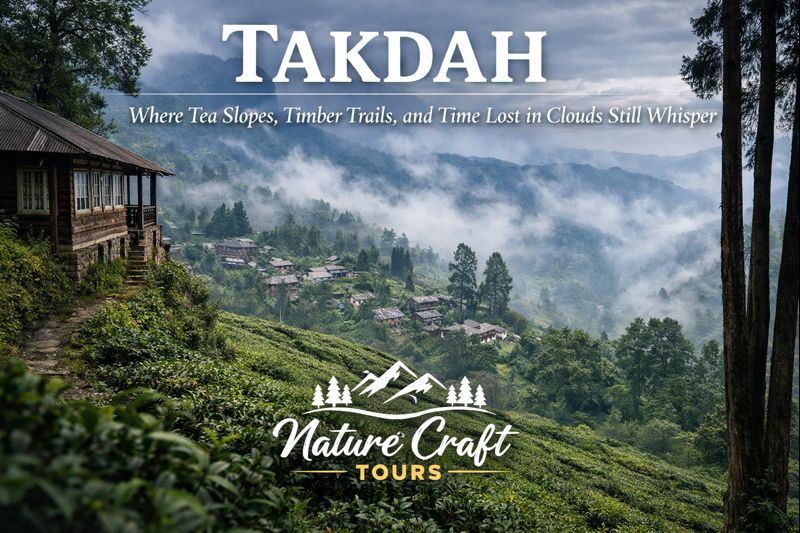

Takdah whispers stories of tea, timber, and time lost in clouds—not loudly, not insistently, but with the patience of a place that has never chased attention. Set high on the lesser-travelled ridges of the eastern Himalayas, Takdah reveals itself gradually, as mist drifts between pine trunks and the contours of old colonial roads fade into forest shade. This is not a destination shaped by spectacle or speed. It is shaped by continuity—of climate, labour, memory, and landscape.

For those who approach Takdah with the mindset of an explorer rather than a consumer, the village offers a layered narrative. Tea plantations still rise and fall along the slopes as they did a century ago. Timber forests continue to define both ecology and economy. And time, slowed by cloud and altitude, behaves differently here—less measured by clocks, more by light, weather, and routine. Takdah is not about what one sees in a moment, but what one begins to understand by staying still.

Takdah in Context: Location and Geographic Character

Takdah lies approximately 28 kilometres from Darjeeling, positioned between the Rangli Rangliot tea belt and the forested corridors leading toward Kalimpong. Its altitude, ranging from roughly 4,000 to 5,500 feet, places it in a temperate ecological zone that avoids both the harsh cold of higher Himalayan settlements and the heat of the plains. This balance has long made Takdah suitable for habitation, cultivation, and strategic planning.

The village is spread across undulating ridges rather than clustered tightly in a single basin. This dispersed layout creates a sense of openness rare in hill settlements, with long sightlines through tea gardens and forests even when visibility is softened by mist. Moisture-laden air from the Teesta valley rises into these hills, ensuring frequent cloud cover, high humidity, and a climate that nurtures both tea and timber.

Colonial Foundations: Timber, Strategy, and Silence

Takdah’s modern form took shape during the British colonial period, when it was developed as a military cantonment and timber zone. Its position allowed for movement between Darjeeling and the eastern frontier while remaining sheltered by dense forest cover. British planners valued Takdah for its cool climate, logistical access, and relative isolation—qualities that continue to define the area today.

Remnants of this period remain embedded in the landscape. Stone-lined roads curve gently along ridges, old barracks and bungalows appear intermittently through the trees, and forgotten footpaths still link forest clearings. Unlike hill towns that expanded rapidly to accommodate tourism, Takdah retained its low-density structure, allowing forest and settlement to coexist without constant negotiation.

Tea as Landscape and Legacy

Tea is not merely an agricultural product in Takdah; it is a defining feature of the land itself. The surrounding tea estates shape slope stability, water flow, and daily human movement. Their terraced geometry contrasts with the irregular forms of the forest, creating a landscape that is both cultivated and organic.

Walking through these tea gardens reveals a working environment governed by seasons and routine. Plucking cycles, leaf quality, and weather patterns dictate daily life, much as they have for generations. The experience offers insight into how large-scale cultivation can integrate with fragile hill ecology when guided by long-established practices rather than short-term extraction.

Forests, Timber, and Ecological Continuity

Takdah is surrounded by mixed temperate forests dominated by pine, oak, chestnut, and cryptomeria. Bamboo groves appear in lower, moisture-rich pockets, while seasonal wildflowers emerge along forest edges. These forests once supported colonial timber extraction and continue to play a role in local livelihoods, though under far more regulated conditions today.

Birdlife is particularly notable. The relative absence of traffic and urban noise allows for frequent sightings of flycatchers, drongos, sunbirds, and hill partridges. In early mornings, sound replaces sight as the primary sensory guide—an experience familiar to those who have explored quieter ecosystems such as the interiors of a Sundarban Trip, where nature communicates through rhythm rather than display.

Approaching Takdah: Routes and Accessibility

Takdah is typically accessed via Darjeeling or Kalimpong. New Jalpaiguri serves as the nearest major railhead, while Bagdogra Airport connects the region to metropolitan centres. From these points, the journey continues by road, passing through progressively quieter terrain as commercial signage gives way to tea estates and forest corridors.

The final approach is telling. Roads narrow, traffic thins, and the pace of travel slows. The shift is not merely physical but perceptual, preparing visitors for a destination where walking replaces driving and observation replaces itinerary-checking.

Best Time to Experience Takdah

Spring (March to May)

Spring brings clarity and colour to Takdah. Rhododendrons bloom along forest edges, tea bushes flush with new growth, and temperatures remain comfortably cool. This season is well suited for walking, photography, and extended exploration.

Monsoon (June to September)

During monsoon, Takdah becomes deeply atmospheric. Mist thickens, forests darken, and rainfall transforms the landscape into layered shades of green. While travel requires caution due to slippery roads, this season offers a rare immersion into the hill ecology—an experience comparable in intensity, though not in terrain, to journeys undertaken during a Sundarban Tour Package in peak monsoon.

Autumn (October to November)

Autumn is marked by stable weather and improved visibility. The retreat of monsoon clouds reveals distant ridgelines, and walking conditions are ideal. This period balances atmosphere with accessibility.

Winter (December to February)

Winters in Takdah are quiet and contemplative. Mornings are cold, often accompanied by frost, while days remain crisp. Mist lingers longer, reinforcing the village’s sense of isolation and stillness.

Ideal Duration for a Meaningful Stay

Takdah is best experienced over three to five nights. Shorter stays allow only surface impressions, while longer durations reveal patterns—changes in light, sound, and weather that define daily life. The village rewards repetition: walking the same road at different hours, observing tea gardens in varying conditions, and allowing silence to become familiar.

Key Attractions and Subtle Highlights

Colonial Cantonment Zone

The old cantonment area remains central to Takdah’s identity. Former barracks, officers’ residences, and administrative buildings stand quietly among trees, their functions altered but their forms largely intact. Exploring this area on foot provides insight into colonial planning philosophies adapted to hill terrain.

Tea Estate Pathways

Informal paths through tea gardens offer some of Takdah’s most immersive experiences. Early morning walks reveal the intersection of labour, landscape, and climate, while late afternoons soften contours and colours.

Forest Trails and Forgotten Routes

Several forest trails trace older movement networks once used for patrols and timber transport. These paths now serve as quiet walking routes, leading through shaded groves and occasional clearings that offer glimpses into the surrounding valleys.

Cultural Fabric and Daily Life

Takdah’s population includes Lepcha, Nepali, and Bengali communities, each contributing to the village’s social texture. Life here is shaped less by tourism and more by agriculture, forestry, and local commerce. Interactions are understated, governed by familiarity rather than performance.

Festivals and rituals are observed within community spaces rather than staged for visitors. This continuity gives Takdah a grounded authenticity, similar to regions where life continues independent of outside attention, such as lesser-visited zones of Sundarban Tourism.

Practical Considerations for Travelers

Takdah requires preparation. Shops are limited, medical facilities are basic, and mobile connectivity can be inconsistent. Visitors should carry essentials, dress for variable weather, and remain flexible in daily planning.

Walking is the primary mode of exploration, making sturdy footwear essential. Weather can shift rapidly, particularly during monsoon and winter months, and mist may reduce visibility without warning. Respect for private land and forest boundaries is crucial.

Takdah Within the Offbeat Darjeeling Circuit

Takdah represents a model of low-impact hill travel. It has resisted rapid commercialization, preserving both ecological balance and cultural continuity. For travelers seeking structured access without compromising the area’s character, curated routes such as the TakdahTour Package offer contextual exploration grounded in local geography and history.

At the same time, independent travelers will find Takdah accommodating to unstructured discovery. Its roads, forests, and silences invite slow movement and careful observation. For a broader understanding of the region’s place within offbeat Himalayan travel, detailed perspectives on Takdah itself help situate the village within its wider landscape.

Listening to Takdah

Takdah does not demand attention. It whispers—through mist drifting across tea slopes, through timber forests absorbing sound, through roads that curve rather than cut. Its appeal lies in restraint, continuity, and the quiet confidence of a place shaped by time rather than trend.

For the traveler willing to slow down, Takdah offers more than scenery. It offers perspective—on how landscapes endure, how communities adapt, and how travel can remain an act of listening rather than consumption. In a world increasingly defined by acceleration, Takdah stands apart, content to remain partly hidden, patiently waiting for those prepared to hear what it has to say.