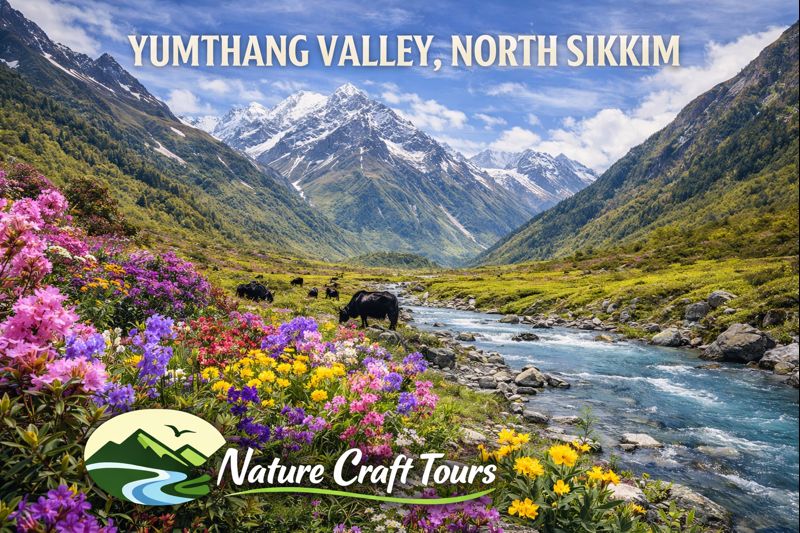

Yumthang Valley, North Sikkim

— The Living Alpine Theatre of the Eastern Himalaya

Far beyond the last permanent settlements of North Sikkim, where roads narrow, air thins, and mountains dictate the rhythm of life, lies Yumthang Valley — a high-altitude basin sculpted by glaciers, rivers, and centuries of seasonal migration. Often introduced superficially as the “Valley of Flowers,” Yumthang is far more complex than a seasonal bloomscape. It is a functioning alpine ecosystem, a cultural corridor, and a living laboratory where geology, botany, climate, and human resilience intersect.

This article approaches Yumthang Valley not as a checklist destination, but as an evolving Himalayan landscape that rewards patient observation. Drawing upon geographical research, ecological records, and on-ground travel realities, the following narrative presents Yumthang as it truly exists — remote, fragile, breathtaking, and deeply instructive for any traveler willing to engage with the mountains on their own terms.

Geographical Context and Location Overview

Yumthang Valley is situated in the northern extremity of the Indian state of Sikkim, within the Mangan district (formerly North Sikkim). The valley lies at an approximate altitude of 3,564 meters (11,693 feet) above sea level and forms part of the upper Lachung River basin, a tributary system ultimately feeding the Teesta River.

Geologically, Yumthang occupies a glacial trough carved by ancient ice flows descending from the Pauhunri and Shundu Tsenpa mountain systems near the Indo-Tibetan frontier. The valley floor remains comparatively broad for this altitude, allowing seasonal grasslands, rhododendron scrub, and riverine wetlands to coexist in rare harmony.

Climatically, Yumthang rests within the alpine-subalpine transition zone. Winters are long and severe, with heavy snowfall rendering the valley inaccessible for several months. Summers are brief but biologically explosive, marked by rapid flowering cycles and active grazing grounds for yaks and sheep.

Historical and Cultural Significance

While Yumthang has no permanent human settlement today, it has long functioned as a seasonal pasture and transit corridor for the Lachungpa community. The Lachungpas, a Bhutia sub-group, historically practiced transhumance — migrating livestock to higher pastures during summer and retreating to lower valleys in winter.

Local oral traditions refer to Yumthang as a sacred grazing ground governed by customary village laws rather than individual ownership. These informal ecological regulations — such as rotational grazing and seasonal access restrictions — predate modern conservation frameworks and have contributed significantly to the valley’s ecological resilience.

A small stone shrine dedicated to local protective deities still stands near the valley floor, subtly reminding visitors that Yumthang is not merely a scenic expanse but a spiritually contextual landscape shaped by belief systems as much as by glaciers.

Ecological Importance and Biodiversity Profile

Alpine Flora and Seasonal Bloom Cycles

Yumthang Valley supports an exceptional diversity of alpine flora, particularly within the rhododendron genus. Over twenty-four species of rhododendron have been recorded in this region, ranging from low-lying shrubs to medium-height arboreal forms.

The flowering season, typically between late April and early June, transforms the valley into a dynamic mosaic of crimson, pink, white, and pale yellow blossoms. Unlike manicured botanical gardens, these blooms emerge in uneven waves, responding to micro-variations in sunlight, snowmelt, and soil composition.

In addition to rhododendrons, the valley hosts alpine primulas, potentillas, saxifrages, and edelweiss-like composites, many of which complete their entire life cycle within a few weeks.

Faunal Presence and High-Altitude Adaptation

Large mammals are seldom visible during daylight hours due to human presence, but indirect signs confirm the presence of Himalayan blue sheep, red foxes, and occasional snow leopard movement along higher ridgelines. Avifauna includes blood pheasants, snow pigeons, and alpine accentors.

Yak herds remain the most visible faunal element, particularly during summer months. These animals are not merely livestock but ecological agents — shaping grassland regeneration patterns through grazing and nutrient redistribution.

Seasonal Variations and Best Time to Visit

Spring and Early Summer (April to June)

This period represents Yumthang’s most biologically active phase. Snow recedes rapidly, exposing fresh meadows and triggering mass flowering events. Daytime temperatures remain cool but manageable, while nights are sharply cold.

Accessibility during this window depends heavily on snowfall patterns from the preceding winter. Delayed road clearance can push effective opening dates into May.

Monsoon Season (July to September)

Although flowering declines, the valley adopts a lush green character during monsoon months. However, heavy rainfall significantly increases landslide risk along approach routes, making travel unpredictable and sometimes unsafe.

Autumn (October to Early November)

Autumn offers crystal-clear visibility, golden alpine grasses, and stable weather. While floral diversity is minimal, the clarity of surrounding peaks provides unmatched photographic and observational opportunities.

Winter Closure (Late November to March)

Heavy snowfall renders Yumthang inaccessible during winter. Roads beyond Lachung are officially closed, and the valley reverts entirely to its natural dormancy.

Ideal Travel Duration and Acclimatization Strategy

A visit to Yumthang Valley should never be rushed. At minimum, travelers should allocate two full days within North Sikkim, including overnight acclimatization at Lachung.

Rapid ascent from lower altitudes increases the risk of acute mountain sickness. Slow progression, hydration, and limited physical exertion on arrival are essential for safe exploration.

Route and Accessibility Details

The standard access route to Yumthang Valley begins from Gangtok, progressing northward through Mangan, Chungthang, and Lachung. Road conditions vary widely depending on season, weather, and ongoing infrastructure projects.

Beyond Lachung, the road ascends sharply along the Lachung River, passing through exposed avalanche zones and glacial runoff channels. Travel permissions are mandatory due to the valley’s proximity to the international border.

Key Attractions Within and Around Yumthang Valley

Yumthang River Basin

The river itself, fed by glacial meltwater, forms braided channels across the valley floor. Its mineral-rich waters contribute to the fertility of surrounding meadows.

Hot Spring Zone

Near the valley’s entry point, sulfur-rich hot springs emerge along fault lines, historically used by local herders for therapeutic purposes.

Seasonal Pasturelands

The open grazing grounds reveal how traditional pastoralism coexists with fragile alpine ecology — an increasingly rare balance in the modern Himalaya.

Comparative Travel Context and Broader Landscape Understanding

Travelers interested in understanding India’s ecological diversity often juxtapose high-altitude Himalayan regions with low-lying deltaic ecosystems. In this context, destinations such as the Sundarban Tour provide a striking counterpoint — showcasing how altitude, hydrology, and biodiversity interact differently across the subcontinent.

Similarly, structured itineraries like the Sundarban Tour Package from Kolkata demonstrate how ecological tourism must adapt to terrain-specific challenges, whether tidal mangroves or glacial valleys.

Practical Travel Insights and Responsible Exploration

Visitors must recognize that Yumthang Valley operates within a narrow ecological tolerance. Waste disposal facilities are nonexistent beyond Lachung, making carry-back responsibility non-negotiable.

Weather can change abruptly, and mobile connectivity is unreliable. Travelers should remain flexible, prioritize safety over schedules, and respect local advisories.

Photography should be approached with restraint, particularly around grazing livestock and religious markers. Yumthang rewards quiet observation far more than hurried documentation.

Yumthang as a Landscape, Not a Landmark

Yumthang Valley is best understood not as a destination to be “covered,” but as a landscape to be interpreted. Its beauty lies not merely in seasonal flowers or snow-lined peaks, but in the processes — ecological, geological, and cultural — that continue to shape it year after year.

For travelers willing to slow down, acclimatize responsibly, and engage with the valley beyond surface impressions, Yumthang offers something increasingly rare: a glimpse into a Himalayan system still governed more by nature than by tourism.